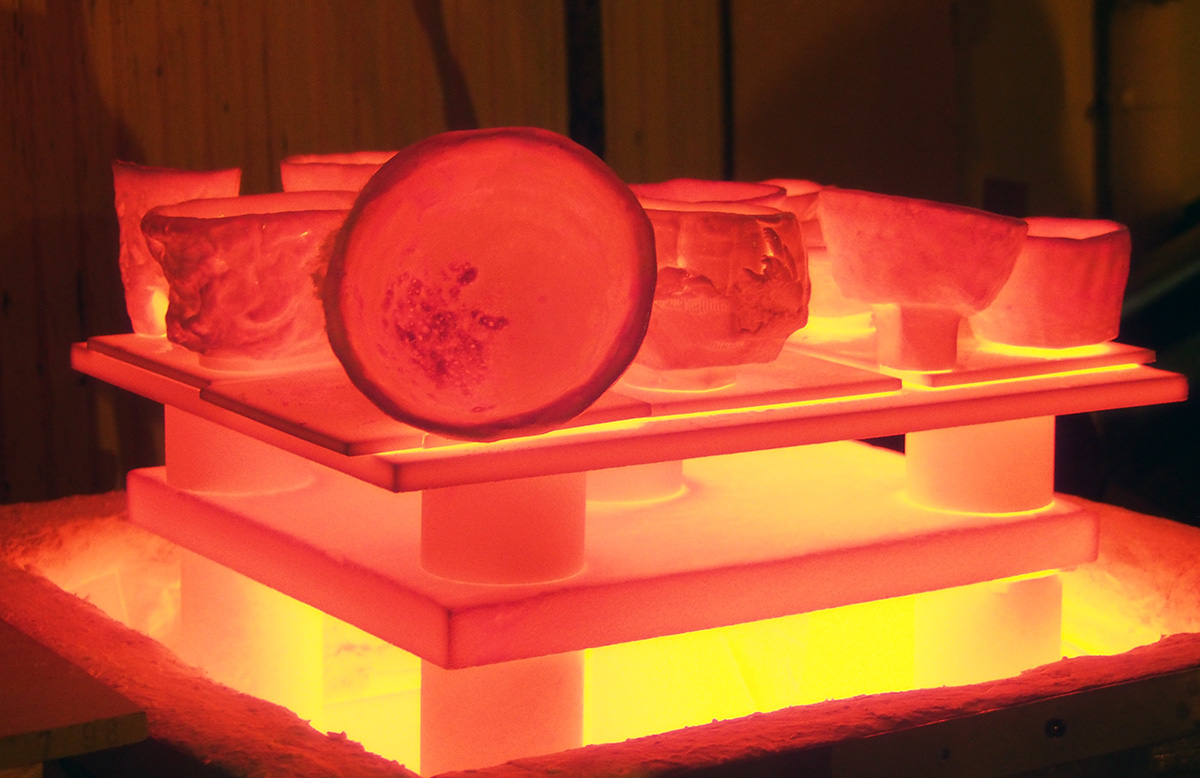

Raku ceramics for the tea ceremony

Raku ceramics emerged in the sixteenth century Japan and is closely related, from a historical point of view, with the tea ceremony and the philosophy of Zen Buddhism. The primitive forms of Raku accentuate the principle of simplicity and naturalness, which derived from the love of nature.

Raku ceramics has its origins in 16th Century Japan when a skilled potter called Chojiro produced bowls (called ima-yaki) for ritual tea ceremonies. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, an influential warrior-statesman, was so impressed by the pottery that he bestowed a gold seal on the family, which incorporated the symbol representing the Chinese character Raku, meaning a feeling of contentment, pleasure and enjoyment but also meaning the very best of the world. The pottery was renamed juraku-yaki and Raku became the family name. In time the family name became synonymous with the ceramics they produced.

Central to the tea ceremony is the ancient aesthetic philosophy of Wabi Sabi, which is rooted in Zen Buddhism. Wabi means things that are fresh and simple or rustic. It also can mean an accidental or happenstance element, maybe even an imperfection which lends elegance and uniqueness to the whole. Sabi means things whose beauty stems from age and stresses the appreciation of transient things and of the cycles of life that give rise to change. Thus the combined word Wabi Sabi means the fascination with things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is the beauty of things modest, humble, and unconventional and perhaps unpretentiousness or a kind of primitive naturalness, where there is a perverse beauty in imperfection.

The ideal bowl for the tea ceremony would exemplify the Wabi Sari spirit and would be devoid of ego and individual expression, revealing instead an abstract, spontaneous, and unassuming nature. Made without a potter’s wheel, the bowls were formed by hand, lacking graceful movement, decoration, or distinction of form.

Thus, Raku is not a technique, but rather the state of mind of the potter while he works. It is a particular way of working the clay, almost letting the clay lead the way and shape itself and guide the hand without conscious thought, while the mind experiences the moment.

Português

Português English

English Español

Español